Perfectionism is a personality trait that is on the increase. Back in the 1980s, psychiatrist Dr David D. Burns rather eloquently defined perfectionists as:

people who strain compulsively and unremittingly toward impossible goals and who measure their own worth entirely in terms of productivity and accomplishment.

Burns, D.D. (1980). The perfectionist’s script for self-defeat. Psychology Today, 14, 34–52, p.34.

It is clear from the above that perfectionism is irrational, anxiety-inducing and ultimately self-defeating. Indeed, as a paper published last year concluded, it is a trap that ensnares both mind and body: ‘Maladaptive perfectionism manifests in cognitive, emotional, behavioural, and physiological responses, potentially leading to emotional and physical exhaustion, as well as physical symptoms through overburdening the stress response system’.

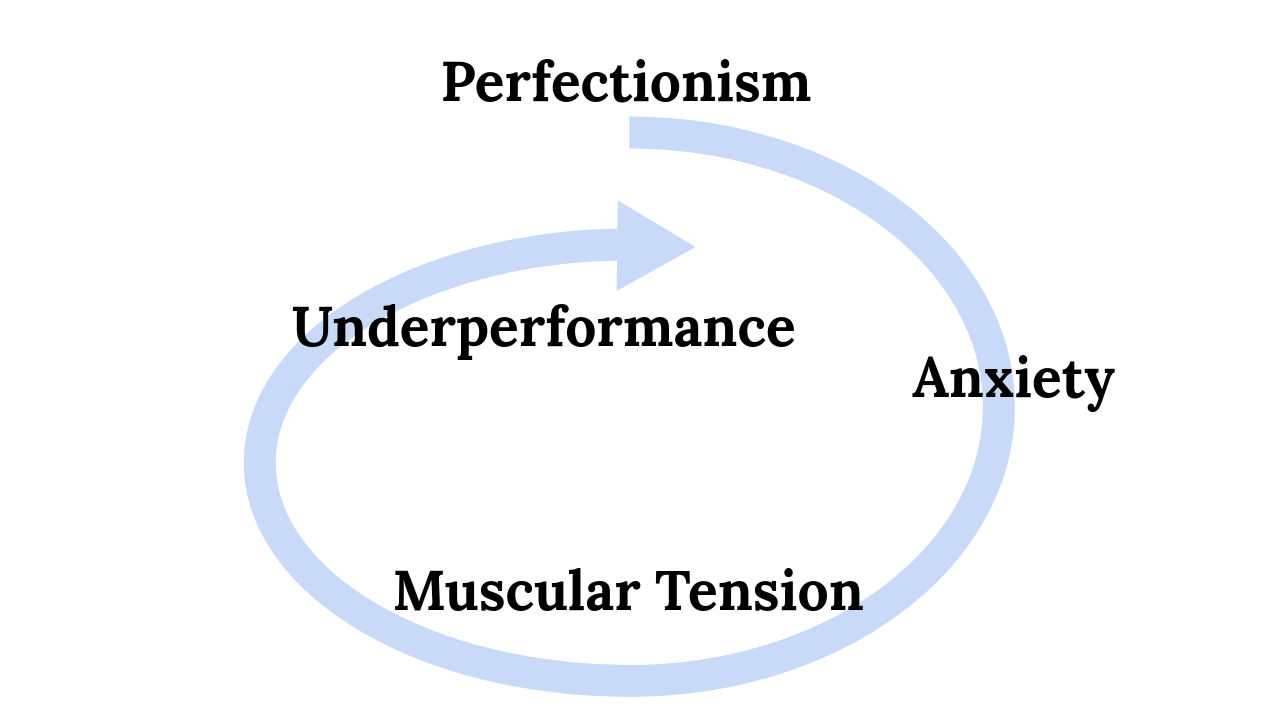

As an Alexander Technique teacher, I’m often working with those in the arts who are under pressure to develop their skills to the very highest level. I’m therefore interested in helping individuals understand that perfectionism is ‘maladaptive’ when developing a complex skill such as a learning a musical instrument. Below is my simple illustration of how perfectionism is self-defeating when learning a physical skill:

Put simply, perfectionism always leads to anxiety, which always leads to muscular tension, which always leads to underperformance. In a recent publication for pianists, Penelope Roskell describes this vicious circle:

Chronic contraction may have set in gradually as a response to anxiety about accuracy. Here we come up against the piano player’s paradox: the more you try to be accurate, the more you contract the muscles in an attempt to control the movement and the less accurate you become.

Penelope Roskell, The Complete Pianist p.79

The Alexander Technique is very good at unwinding such a negative cycle. Firstly, it recognizes that our mental, emotional and physical selves are all deeply intertwined. This means that it is well-placed to tackle a phenomenon like perfectionism which adversely affects all three.

Secondly, the Alexander Technique recognizes that the performance of a part (for example the arm or fingers) depends on the health of the whole organism. Put simply, this means that inappropriate holding in one part of the body will adversely affect the quality of movement somewhere else. Instead, skilled performers need to establish both appropriate and adaptable muscular tone throughout their entire physical selves. Only then can they discover greater freedom, quality and strength in discrete movements.

The Alexander Technique puts the value of a properly functioning whole front and centre, and habits of mind and body which interfere with this properly functioning whole are gradually dealt with. This includes the corrosive habit of perfectionism.

Here is not the place to describe how the Alexander Technique works. Yet it is worth understanding that to deal with something like perfectionism requires a wholesale change in one’s perspective on what one is doing. In his latest book, Iain McGilchrist hints at what this might be like, firstly with a beautiful quote from ancient Chinese, and secondly with reference to how our two brain hemispheres can attend to the world in radically different ways, and how this can alter the quality of what we’re doing:

Even heaven is not complete; that is why when people are building a house they leave off the last three tiles, to correspond. And all things that are under the sky have degrees. It is precisely because creatures are incomplete that they are living.

Ssu-ma Ch’ien, Historical Records (Shih chi), c.100BC. Cited in Iain McGilchrist, The Matter With Things p.840.

‘Perfect’ literally means completed – done with. The achieved infinite of the left hemisphere is unreal (can never be achieved) and is lifeless; the constantly becoming, processual, infinite of the right hemisphere is real and life-giving. Note that this is an inversion of what we normally hold, namely, that potential means unreal, and actual means real … It seems to me, that, as usual, when it comes to the nature of Being, or God, we are easily attracted to, and too readily comforted by, the idea of a fully achieved perfection, rather than one of open dialectical creativity, continually both expressive and receptive.

Iain McGilchrist, The Matter With Things p.1247.