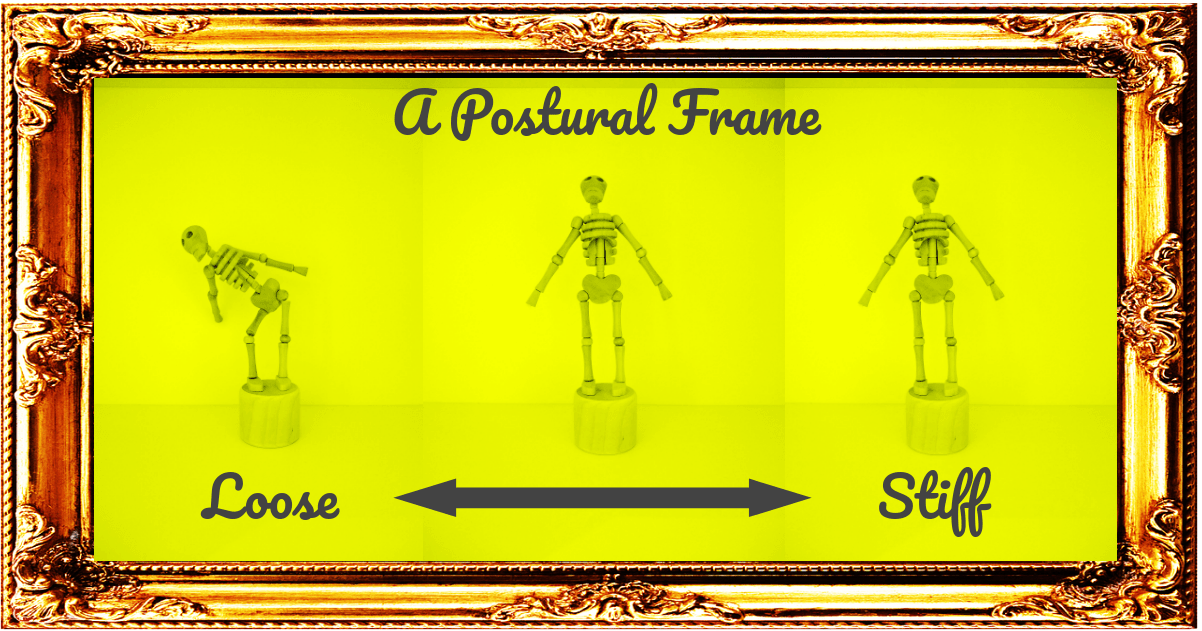

I have a new teaching aid: a miniature ‘push puppet’ skeleton. Left on its own, the skeleton stands very stiffly, held taut by internal elastic strings. Push the button at its base and the skeleton collapses into a heap.

But there is also a third unexpected condition. You can push the button underneath just a little and the skeleton retains its default posture with less tension.

The following illustrates what can happen:

‘Same posture, less tension’

The push puppet skeleton mirrors what can happen in humans. For example, can you remain in your current posture right now, but with less tension? Why not test out the idea by closing your eyes, releasing your breath and slowly scanning down your body to see what you’re holding on to.

A person can hold the same position either freely or with tension. In fact, if someone’s postural system is working well, they’re not really holding a position at all. They are in tune with their innate ability to release and rebalance instead of hold positions chronically.

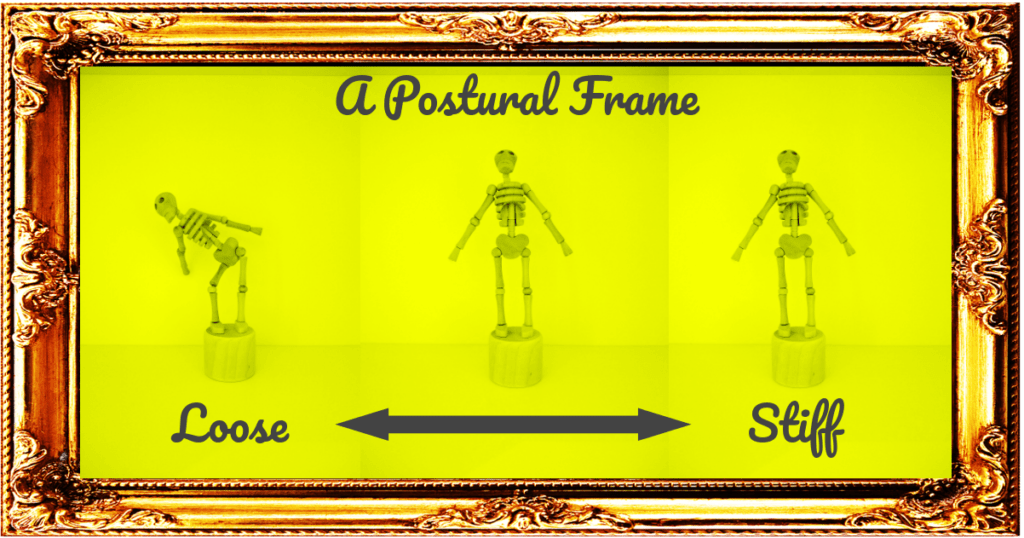

This principle is based on research into postural muscle tone, which is the continuous, low-level muscle activity required to keep us upright in relation to gravity. According to a recent article, postural tone provides

an “adaptive frame” that readies the nervous system and body for movement. If the frame is too stiff, we must overcome our own resistance to act in the world. If the frame is too loose, we act without the necessary stability and support. The concept of “tone as readiness” was first proposed by the pioneering motor control scientist Nikolai Bernstein in 1940.

Cacciatore, Cohen & McCann, ‘Mind the Gap: The Missing Science of Posture’

‘Doing good posture’: the elastic band problem

Scientists have suggested holding a simple posture takes only 3%-5% of the maximum muscle capacity (ibid.). What therefore seems to be going wrong for a lot of people?

Often, people try to ‘do’ good posture. For example, they’ll try to pull back their shoulders and sit up straight, only to find that they’ve returned to a slump minutes or even seconds later. It’s understandably really frustrating, and so they might latch onto the idea that they need to ‘strengthen their core’ to maintain a ‘correct’ posture.

And yet what is often not considered is that muscles can be chronically tense to begin with. This means that any effort to come out of a slump is destined to fail: the shortened, tense muscles ping us back to where we began, like a stretched elastic band. This sense of fighting ourselves is called co-contraction.

It therefore becomes clear that just ‘doing something’ doesn’t really cut it.

Change and the postural system

If you sense that chronic tension or poor posture is interfering in your life, the good news is that the postural system is open to change. The process of change, however, might be one that defies your expectations.

For example, there is evidence that applying the Alexander Technique helps postural muscle tone become more adaptable and better distributed through the body. It changes the underlying patterns that support and facilitate the movements we make.

But the Alexander Technique achieves its effects through a process called inhibition: that is, pausing to prevent unnecessary tension, ‘doing less’, or even ‘non-doing’. We are all the victim of habits, and often cannot see beyond them. But getting help to stop and ‘not do the pattern’ can open up new possibilities in unexpected ways.

Indirect changes in alignment

I began this blog by suggesting that we could maintain the same position, or posture, but with less tension. While that is true, you would probably also wish to widen out your postural repertoire. Freedom from tension gives you the option of releasing into length and width, more of the time.

For example, below is a student I worked with for the first time for only 15 minutes. You can see that he is enjoying being taller and more released, and he would be able to rediscover it more often with further work.

The changes in alignment such as the above are indirect: they are not the result of someone voluntarily holding a position, but rather the result of being guided beyond habits of tension.

Conclusion

So, indeed, our postural system is able to change but perhaps not in the way you might imagine. Reducing unnecessary tension, rather than introducing more tension into an already tense system, is a good starting point.

It’s counter-intuitive, but then so is the idea that a simple push puppet could release some of its tension and yet maintain the same posture.